Imago Mundi: A 2,600-Year-Old Map is Rewriting History—But Are We Reading It Wrong?

Archaeologists have uncovered what may be the oldest world map, and it’s not what we expected.

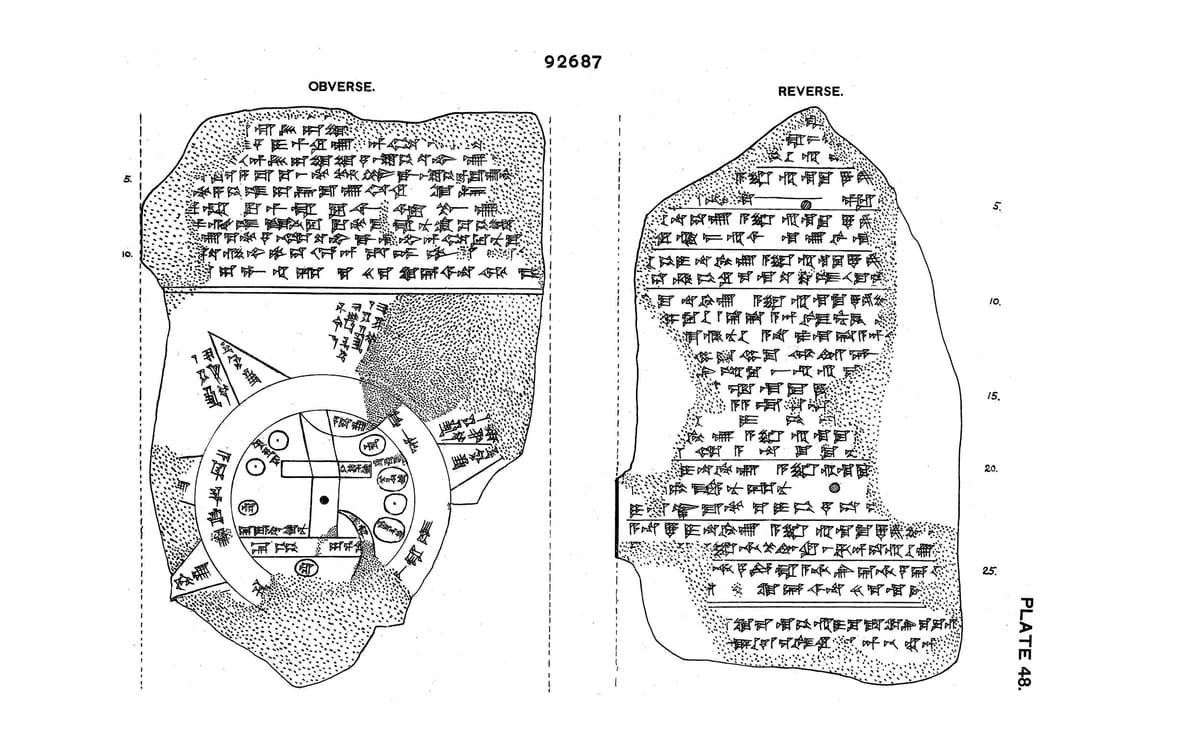

The Imago Mundi, a 2,600-year-old Babylonian clay tablet, doesn’t just depict land and water—it blends mythology, astronomy, and geography into one vision of the universe. But as scholars decode its secrets, new questions arise: Was this really a map? Or was it something else entirely?

The Imago Mundi was discovered in Sippar, an ancient Babylonian city along the Euphrates River, and is now housed at the British Museum. It places Babylon at the center of the world, surrounded by seven cities, mountain ranges, and “bitter rivers” that likely represented vast seas. But beyond its borders lie mysterious lands inhabited by supernatural beings—half-scorpion guardians, divine birds, and gods who ruled the cosmos.

For centuries, scholars assumed ancient maps were practical tools, guiding travelers and merchants. But this discovery challenges everything. The Babylonians didn’t just map land—they mapped power, mythology, and even celestial forces. The back of the tablet contains astronomical inscriptions, linking earthly geography to the stars, reinforcing the idea that Babylonians saw their world as an interconnected cosmic system.

But here’s where it gets complicated: Was this even meant to be a navigational tool? Some experts now believe the Imago Mundi wasn’t a map at all, but a theological statement—a way for Babylonian rulers to assert their dominance, not just over land, but over the heavens.

Why does this matter today? Because it redefines the origins of mapping. It suggests that maps were never just about direction—they were about belief, power, and control. The Babylonians saw their empire as the heart of the world, much like later societies positioned themselves at the center of their own maps.

As researchers continue studying the Imago Mundi, we may have to rewrite the history of cartography altogether. Was this tablet the first step toward modern maps? Or was it a political tool disguised as geography? The more we learn, the more the lines between myth and reality blur.

ART Walkway News